Gabriel Garcia Moreno was the President of Ecuador from 1861 to 1865 and from 1869 to 1875. He was well educated – a chemistry professor – unlike most of the Ecuadorian Presidents who preceeded him, who came from military backgrounds. He was about ten years old when Ecuador became an independent nation-state and he witnessed considerable chaos and lawlessness in Ecuador’s early days.

Although Ecuador won independence from Spain in 1822, the strong Church influence that was an inseparable part of Spanish Culture continued to permeate Ecuadorian Culture after the independence – but it was controversial, of course. Those who opposed strong Church control over Ecuadorian Society were branded “liberals” and those who supported it were dubbed “conservatives”. Garcia Moreno favored strong church control and…

“By the 1840’s [Garcia Moreno] was making a name for himself as an intelligent, eloquent conservative who railed against the liberalism that was sweeping South America. He almost entered the priesthood, but was talked out of it by his friends. He took a trip to Europe in the late 1840’s, which served to further convince him that Ecuador needed to resist all liberal ideas in order to prosper. He returned to Ecuador in 1850 and attacked the ruling liberals with more invective than ever.”

–from Herring, Hubert. A History of Latin America From the Beginnings to the Present. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962

Soon after his return from Europe, he was elected Mayor of Quito. By 1861 he had siezed the Presidency of Ecuador. Historian Herbert Herring summarizes Garcia Moreno’s religious-political approach as follows:

“García Moreno believed that only by establishing very close ties to the church and the Vatican would Ecuador progress. Since the collapse of the Spanish colonial system, liberal politicians in Ecuador and elsewhere in South America had severely curtailed church power, taking away land and buildings, making the state responsible for education and in some cases evicting priests. García Moreno set out to reverse all of it: he invited Jesuits to Ecuador, put the church in charge of all education and restored ecclesiastical courts.”

–from Herrrig, Hubert “A history of Latin America” New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962

More precisely, Garcia Moreno’s conviction -in his own words was that:

“to moralise a country one must give it a Catholic Constitution, and, to ensure the necessary cohesion, a statute of unity.’ ….civilization, ‘the fruit of Catholicism, degenerates and becomes impure in proportion as it departs from Catholic principles …religion is the sole bond which is left to us in this country, divided as it is by the interests of parties, races, and beliefs.”

–quoted in Calderon, “Latin America, its rise and progress” -Chapter 2 (1913)

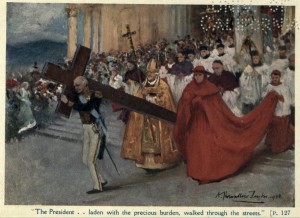

President Garcia Moreno carying a cross at the head of a religious procession in 1873

–from Maxwell-Scott “Gabriel Garcia Moreno: Regenerator of Ecuador” pub. 1914)

Garcia Moreno is credited with bringing several modernizations and improvements to his country. But he had a very serious blind spot on the subject of freedom of conscience or religious freedom. Furthermore, many of his most important improvements were really useful or available to Catholics only. Education is a prime example. Garcia Moreno truly introduced improvements to education in Ecuador. But education was entirely Catholic in character with the Inquisition’s Index of Forbidden Books controlling the literature that students might see and rigid ecclesiastical control over any groups that might be formed – whether on a college campus or elsewhere. Similarly, Ecuador had a very serious problem with extramarital relationships 1 and the resultant out-of-wedlock births. Garcia Moreno tackled this problem also but his solution was to criminalize the out-of-wedlock relationships – insisting on marriage – and only Catholic marriage was allowed; non-Catholics would have to renounce their faith or their children would be branded as “illegitimate” and be unable to inherit2. Worse yet, he excluded “illegitimate” children from education, as testified by a contemporary North American author:

There are no common or free schools in the capital… In 1861, French friars were imported3 to teach boys the rudiments of knowledge; but the education of poor girls is still left to private charity. The number of those who cannot read or write must be enormous. Parents are not required to send their children to school; on the contrary, illegitimate children were excluded by an order of President Garcia Moreno, from the schools of the French friars. Besides, the system of education which now prevails is very bad. In the elementary schools nothing is taught but reading, writing, religion, and a little arithmetic. In the higher schools, Latin, and perhaps Greek, monopolize the time of the student. Geography is taught without maps. The natural and mathematical sciences are neglected, and every deference is paid to religious intolerance. As a proof of this, I shall refer to but one instance. For many years, Vattel’s “Law of Nations”4 was a text-book at the University. Several years ago, however, the Archbishop remonstrated against the use of it as heretical, because it advocates religious toleration. It was immediately prohibited, and Bello’s meagre essay5 substituted in its place.

–from Hassaurek, F – “Four years among Spanish-Americans” p.207 (pub. 1867)

But the most serious problem with Garcia Moreno’s presidency was his insistence on concluding a “Concordat” with the Roman Catholic Pope, granting enormous power to the Church in Ecuador. Sydney Z. Ehler, author of “Church and State through the Centuries” -an excellent scholarly survey of Concordats and Church-State relations worldwide down through the Centuries – bluntly states that the Ecuador Concordat was -from the Church’s point of view- “the most favourable ever concluded with any modern State.” For the full text of the Concordat click here and for commentary on the Human Rights violated by the Concordat, click here.

To further reinforce the theocracy Garcia Moreno created, he also arranged for a new constitution to be drawn up. Under Garcia Moreno, Ecuador’s Constitution decreed that:

…no one was to be elected or eligible [for public office] who did not profess the Catholic religion, and whosoever should belong to a sect condemned by the Church would lose his civil rights.

— Calderon, “Latin America, its rise and progress” -Chapter 2 (1913)

This same constitution:

” …made Roman Catholicism a prerequisite for citizenship, conformed to Pope Pius IX’s anti-liberal Syllabus of Errors, and pledged to make ‘political institutions’ conform with ‘religious beliefs.’ ”

–from Derek Williams “The Making of Ecuador’s Pueblo Católico, 1861-1875”

It’s no wonder that Garcia Moreno’s 1869 constitution was dubbed “The Charter of Slavery to the Vatican”6.

In 1873, after Rome and the Papal States had been taken from Pope Pius IX by the King of a newly united Italy, President Garcia Moreno of Ecuador addressed a note of protest to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the King of Italy expressing his displeasure.

A glimpse into Garcia Moreno’s methods may be seen from the manner in which he forced Roman Catholic practice on Ecuadorian Government officials:

“García Moreno strictly legislated compulsory Church attendance for public officials during holidays. In part, this was a symbolic demonstration of Church-state harmony, but it also ensured that local authorities were practicing—if not devout—Catholics.i The central government actively developed a network of surveillance to detect impious behavior of local officials.”

–from Williams, Derek “The making of Ecuador’s Pueblo Catolico(2005)”

His supporters saw him as “a potent organizer” and “the regenerator of his country” and Garcia Moreno righteously proclaimed “Twenty-five years are needed to establish my system”.

But in 1875 President Garcia Moreno was brutally attacked and assassinated by a small group of assassins. As one recent Historian -Hubert Herring- has expressed it, in the years after Garcia Moreno:

…the government of Ecuador fell apart for a while as a series of short-lived dictators took charge. The people of Ecuador didn’t really want to live in a religious theocracy…

Another commentator would later remark that in the years after Garcia Moreno’s assassination civil wars were started leading to…

“…almost a quarter of a century of fighting, the complete exhaustion of the resources of the country and the loss of many thousands of valuable lives.”

–from Webster E. Browning Ph.D. “The Republic of Ecuador, Social Intellectual and Religious Conditions today.” (pub. 1920)

This period of “almost a quarter century” refers to the two-decade period from 1875 to 1895. It was in the year 1895 that Eloy Alfaro was first elected to the presidency.

- In Colonial and post-Colonial Ecuador a marriage could be solemnized only by a Roman Catholic priest. But the priests demanded a fee to perform even the simplest ceremony. The fee was so high that the lower classes could not afford it – and it was “cash only”; as one contemporary observer put it, the priest “never trusts”. This resulted in a considerable number of young people initiating cohabitation before solemnization – typically with the hope of some day having enough money to pay the priest. Although a surprising number of these unions endured, a significant number of them didn’t and either way, children born before solemnization would be branded as “illegitimate” in a culture which forced them to wear the label forever. ↩

- For more coverage of the subject of Marriage in 19th Century Ecuador consult a 1907 Publication by John Lee M.A. entitled “Religious liberty in South America” ↩

- These French friars had been imported by President Garcia Moreno ↩

- The text of Vattel’s “Law of Nations” is avalable here ↩

- The reference here is to Andres Bello (1781-1865), a South American philosopher who wrote a treatise on International Law. In 1953 the Andrés Bello Catholic University was founded, named in his honour ↩

- This is cited in Spindler and Cook “Selections from Juan Montalvo Translated from the Spanish” p.108 ↩