Birth and Ethnicity

Eloy Alfaro was born in 1842 in Montecristi, Ecuador. According to the Encyclopedia of World Biography:

His father, Manuel Alfaro, was a Spaniard who came to the town as a buyer of straw hats and settled down to live with Natividad Delgado, a girl with mixed white, Indian, and African ancestry. They had eight children, and their common-law marriage was legalized through a church wedding in 1863.

–from https://www.bookrags.com/biography/jose-eloy-alfaro/

Early Years

When Eloy was twenty years of age (1862), Ecuadorian President Garcia Moreno was in the process of turning Ecuador into a near theocracy by granting great powers to the Clergy and the Catholic Church through a Concordat and a revised constitution. Although Moreno was assassinated in 1875, Ecuador remained bitterly divided over the church-state issue after his death. So over a period spanning more than thirty years of Alfaro’s adult life, he was either campaigning (often militarily) against these “conservative” governments of Ecuador, or living in exile in Panama as a result of his revolutionary activity. His wife was a Panamanian and her personal wealth sometimes supported or assisted his revolutionary activities. He had also been successful in some early business ventures. When the assassination of Garcia Moreno was being planned in 1875, the assassins -according to R. Perez Pimentel- invited Alfaro to join in their plan but he declined.

To the end of the 19th Century

Later, in 1884, during the presidency of the pro-Catholic (“conservative”) President Caamaño, Alfaro organized an armed revolutionary expedition aimed at the overthrow of Caamaño. After these episodes Alfaro would typically flee across the border – often into neighboring Columbia. In 1886 he was in Peru (Lima) for a time and it was here that he met Dr. Francisco Martinez who had been exiled from the country by the Caamaño government due to his publication of “El Perico” – a weekly publication that was exposing the folly of the “conservatives” in an indirect way.

By 1886 there was an attempt on the life of Caamaño and a brief notice appeared about it in the New York Times mentioning also that Caamaño had escaped to Guayaquil and that after his arrival a disturbance occurred with some of his political opponents and that shouts of “Vive Alfaro” had been heard.

The “Progressives” and Alfaro’s rise to Power

Caamano’s term as president ended in 1888 and during the next seven years Ecuador was ruled by two “Progressive” presidents. The “Progressive” movement was an attempt within the conservative party to moderate the hard-lined “conservative” position; the “Progressives” formed a coalition with the “conservative” party.

But in 1895, during the presidency of Luis Cordero Crespo, the “conservatives” revolted and the coalition split. 1 At this point the “Liberals” came together and seized their opportunity. They then called back Eloy Alfaro from Panama; eventually, he marched with his army on Quito and was soon established as President. Alfaro set to work seriously dismantling the human rights abuses of Garcia Moreno and called for a rewriting of the constitution. A. Kim Clark’s version of the story is:

In the aftermath of the scandal that triggered the Liberal Revolution in 1895, President Luis Cordero was compelled to resign. His resignation was forced by a conservative uprising, but, once they had initiated it, the conservatives could not maintain control over the process. The country disintegrated into factions, and coastal elites called on General Eloy Alfaro to return from exile and assume command. Alfaro led the liberals to power and became the great leader of the Liberal Revolution.

–from A. Kim Clark “The redemptive work: railway and nation…”

The Constitution amended under Alfaro

Under Eloy Alfaro the Ecuadorian Constitution was ammended to undo the long-neglected damage done during the rule of President Gabriel Garcia Moreno:

Some of the articles of the Constitution which were enacted, with special reference to the pretensions of the clergy, may be quoted as follows:

“Article 16: Instruction is free, with no other restrictions than those pointed out by the respective laws, but all instructions given by the State or the municipalities is essentially civil and lay. Neither the State nor the municipality shall give a subsidy to, nor help in any way whatever, any instruction that is not official or municipal.”

“Article 18: The Republic recognizes no hereditary positions or privileges, and no personal prerogatives. It is prohibited to fund mayoralties of any kind of organizations which may hinder the free transfer of property. Therefore, there cannot exist in Ecuador any kind of property which cannot be sold or divided.”

“Article 26: The State guarantees the following:

Section 3. Liberty of conscience in all its aspects and manifestations, so long as these are not contrary to morality nor subversive of the public order.

Section 16. Liberty of thought, expressed by word, or in the press.”

“Article 28. Foreigners shall have the same civil rights as Ecuadorians, and the same constitutional guarantees, so long as they respect the constitution and the laws of the Republic.”

-Browning “Republic of Ecuador” p.8

The ban on Protestant Missionaries was also lifted:

…the Alfaro regime lifted the centuries old ban on Protestant evangelism in Ecuador, and welcomed Protestant missionary groups into the country from 1895 onwards. Labelled “Children of Satan”, the Protestant missionary groups, with their different religious agenda that excluded the opulence, magnificent churches and unquestioned power associated with the Catholic Church in Ecuador, directly threatened the traditional Catholic monopoly over religious affairs in Ecuador, thereby generating considerable resistance and opposition from the Catholic clergy.

–from Steynms “OIL POLITICS IN ECUADOR AND NIGERIA… ” (Phd. Thesis : 2003)

Alfaro and the Railroad

In Alfaro’s time Ecuador still had many problems; poverty and a lack of unity among them. Garcia Moreno had tried to remedy the disunity problem by forcing Catholicism on the Ecuadorians. Alfaro insisted on freedom of conscience but he was also aware of the disunity problem and he believed that it could solved -at least in part- by a railroad connecting the country’s two most important cities: the capital of Quito two miles up in the Andes and the magnificent port city of Guayaquil down at sea level. He also saw this railroad as a serious way to address the poverty problem as the natural resources of the country were vastly underdeveloped and the railroad was badly needed. The trip between the mountain Capital and the Coast was an arduous journey of several days.

Very early in his presidency -in 1896- Eloy Alfaro started his search for railway contractors and work on the railroad was started after the contract with Archer Harman was signed in June 1897. Landslides in the rainy season of 1900 destroyed the work done up till that time and the original route was changed to cross the Chanchan River…

The Chanchan was crossed twenty-six times by the rail line, which ascends 3,050 meters in 80 kilometers… The Guayaquil-Quito Railway turned out to be one of the most expensive railways in the world. In fact, it only operated at a profit for a few years in the 1920’s and again in the 1940’s. Nonetheless, this railway was to become the principal artery of a national integration in Ecuador. Not only did it allow the economic integration of the national territory, but it also provided a political and discursive field within which the Ecuadorian elites could build consensus about their national project.

–from A. Kim Clark, “The redemptive work: railway and nation in Ecuador 1895-1930”

Hear the sounds of the railroad at the Ecuadorian Railroad Company Website.

Alfaro not irreligious

Alfaro was not irreligious or opposed to Religion. In fact the following contemporary account of him appeared in the early 1900’s:

It is a tradition throughout this region of South America that he owed his liberal attitude to a study of a copy of the Bible, which was given him by a traveling missionary, Dr. Marwin, a Presbyterian, who met him on one of the coast boats. However true this may be, I was told by one who knew him well, that he never failed to read at least a chapter each day from the Book, and that he lost no opportunity to recommend its study to others. There was no one to instruct him, however, and he seems to have tended to a spiritistic interpretation and believed that he was being led and directed by some familiar spirit2.

-Browning “Republic of Ecuador” p. 5

The close of the Alfaro Epoch

President Plaza and the Liberal Split

Alfaro’s first term closed in 1901 with the the transfer of power to the new president Leonidas Plaza. Although Plaza had credentials in Liberal circles, he was not fully committed to some of the key principles that Alfaro and his closest circle regarded as absolutely essential. From the beginning, the goals of the Alfaro strain of the Liberal Movement were clear. In addition to a long list of reforms related to the issue of Church power and influence in Ecuador, Alfaro and his closest circle were openly committed to ending the brutal exploitation of economically disadvantaged classes in Ecuador and to freedom for the Indigenous Peoples. Although the religious and economic spheres could be viewed as two separate spheres, in many ways they had considerable overlap in Ecuador.

“The various orders of the Catholic Church together made it the largest landowner in the highlands during the nineteenth century. At the end of the century the landed properties of religious communities numbered eighty-six in eight highland provinces with a total value of more than ten million sucres. This was not simply a colonial remnant: the church had actually increased its presence in highland agriculture after the 1864 concordat between the Vatican and the Ecuadorian government signed under Garcia Moreno. This agreement allowed the church not only to acquire properties but also to preserve and expand them under the protection of the state…

…Liberals condemned the inactive nature of church wealth. The nationalization of the properties of religious orders in 1908 was commonly referred to as the ley de manos muertas 3, where the state seized estates from the “dead hands” of the Catholic Church.

…As a landowner, the church was also seen as rigidly controlling labor in the highlands, workers whom the liberals believed would be better employed on the coast. But more generally there was the perception that the church aimed to keep people “in their place,” both by promoting a hierarchical society and by discouraging any physical movement of the faithful that might expose them to new ideas.” (Clark, p. 58-61)

Although Plaza vigourously pursued reform in the religious sphere, his approach was completely different in the economic sphere. Plaza was married to “Señora Avelina Lasso, a member of one of the richest aristocratic families, with holdings in several provinces, mainly in Cotopaxi”4; he amassed a great personal fortune. But although Plaza shared Alfaro’s commitment to secular/religious reforms, he was much more interested in consolidating his political base than in securing socioeconomic reforms and rights for Ecuador’s working poor. Plaza proceeded to consolidate his political base by making guarantees to the landowners and the coastal oligarchy all at the expense not only of the working poor but of Alfaro and his closest circle who were increasingly isolated as the more “radical” branch of the Liberal party. Plaza’s conduct is particularly egregious in view of the fact that Alfaro had risen to power risking his life and limb in decades of military struggles against the entrenched oligarchy and forces of religious orthodoxy while Plaza had risen to power relatively easily on Alfaro’s coattails. Plaza was clearly the focal point of a split in the Liberal Party that crystallized throughout his presidential term of 1901-1905. As his term drew to a close, a successor was groomed who could be relied upon to continue the policy of guarantees to the landowners at the expense of the peasantry. This successor was Lizardo Garcia; he was politically weak and within weeks of his inauguration Alfaro managed to overthrow him in a coup known as “the Twenty Day Campaign”. Historian Enrique Ayala Mora has produced comprehensive coverage of the twenty day campaign. We have translations of a shorter account from Ayala Mora and his more detailed acccount..

Some historians have argued that this twenty day campaign is proof that Alfaro was motivated by a lust for raw dictatorial power. This argument fails to recognize the clear fact that Alfaro had repeatedly risked his life -and even spent time in prison- to bring basic freedoms to Ecuadorians and that he was determined to lift the crushing burden from the shoulders of the economically disadvantaged classes in Ecuador. Now he was forced to watch as this aspect of his movement was gradually eroded throughout the term of President Plaza and further jeopardized by the elevation of Lizardo Garcia. So although it’s difficult -if not impossible- to defend the methods he resorted to in his efforts to rescue his program, his motives are quite clearly those of a man determined not to see his life’s work -and the fate of millions of disadvantaged Ecuadorians- undone by the ambitions of a few politically powerful elites who cared little for the fate of Ecuador’s disadvantaged masses. Throughout his life he was fully aware of the fact that the entrenched powers of Ecuador were not going to yield through constitutional or ideological channels alone and the struggles of the Luchador were, more often than not, military in nature. So he undoubtedly saw this twenty day campaign through the same lens as his lifelong struggles against a powerful and unyielding opponent.

Alfaro’s Second Term and the coup

Although Alfaro was ideologically committed to remedying the plight of the peasantry, economic realities are often beyond the control of a single president and his administration. Although the railroad significantly improved economic conditions in Ecuador, it had been bitterly opposed by many landowners fearful that they might thereby lose control over the peasantry; so it became the cause of considerable rancor, and the onerous expense of the project supplied ideological ammunition to its opponents. Over time Alfaro was unable to effect the economic changes necessary to ameliorating the plight of the economically disadvantaged sectors of Ecuador and as a result a significant portion of his political base gradually abandoned him. He was no friend of the religious hierarchy and the landowners recognized him as their most formidable opponent- more so now that Plaza represented an alternative. As his first term drew to a close in 1911, even the Army had abandoned him5 and in August of that year, just a few weeks before the close of his term, he was overthrown by a military coup6. The year preceding his exit had been occupied with identifying a suitable successor 7and he very reluctantly agreed to groom Emilio Estrada to succeed him. But Estrada was not a healthy man and in late December – a mere two months into his term – he died of a heart condition leaving a very dangerous and precarious power vacuum in Ecuador. On the same day Estrada’s death was announced, General Leonidas Plaza launched his campaign for the presidency8. But though Alfaro was out of the country, the “Alfarista” strain of Liberalism was not dead. By the end of the week – by December 28th – three power centers were claiming the Supreme Power in Ecuador: General Montero in Guayaquil (a staunch supporter of Alfaro), Alfaro’s somewhat estranged nephew Flavio Alfaro in Esmereldas province, and Senate President Carlos Freile Zaldumbide now at the helm in Quito.

General Montero’s Provisional Government in Guayaquil

Originally General Pedro Montero, commander of the Guayaquil garrison and a staunch supporter of Alfaro, had considered supporting the constitutional government in Quito but he felt that under the circumstances, the danger of a takeover by Plaza was just too great and seven days after the death of Estrada, on December 28, 1911 he proclaimed himself “Supreme Commander” and promptly formed a presidential cabinet including Dr. Francisco Xavier Martinez Aguirre as his minister of Defense (Ministerio de la Guerra).

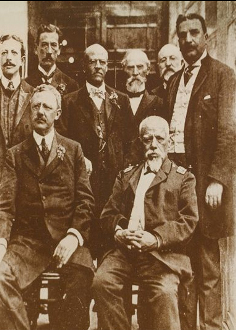

Dr. Francisco Martinez Aguirre (right) and his son Miguel Martinez Serrano (left) (-photo: from grandson John Connolly)

Dr. Martinez’ son Miguel Martinez also held a position in this brief provisional government and when General Montero decided to send a telegram to Eloy Alfaro (who had left the country after the coup and was then residing in Panama), Miguel handled the sending9 of this telegram:

“Following your advice not to let the liberal party falter I have accepted that the people have nominated me as Supreme Commander, but always under orders from you and I hope that you will come on the first steamer so that I can hand over the army to you.”

This was followed the next day by another telegram telling Alfaro that his presence back in Ecuador was urgently needed and requesting that he take an express steamer if necessary.

In the next four weeks, events moved swiftly. Alfaro returned, and his nephew Flavio -somewhat reluctantly- agreed to collaborate with Montero. Meanwhile, in Quito temporary president Freile Zaldumbide placed Plaza in command of the Army sending him down to Guayaquil to quell the rebellion led by Montero. Plaza was now wearing the dual hats of political candidate for an upcoming presidential election while simultaneously head of the military forces challenging the political opposition. This reduced the situation to a struggle between two rivals: the forces loyal to General Montero in Guayaquil and the constitutional forces – under Plaza – still loyal to the central government in Quito. Alfaro, who had agreed to stay out of politics on the occasion of the coup in August, attempted to take on the role of mediator or peacemaker but he strongly urged all sides to move toward a civilian candidate for the presidency rather than yet another candidate who had ties to the military; this met a very cold response. The two sides fought three battles on January 11th, 14th and 18th. This third battle on January 18th which was fought in Yaguachi10 was one of the bloodiest in the history of Ecuador; Montero’s forces lost badly. At this critical juncture several important events took place:

- The next Day, January 19th, Eloy Alfaro was appointed Director of the War.

- On hearing of the disaster of Yagauchi, Dr. Francisco Martinez Aguirre left the country immediately – thus abandoning his Cabinet post as Minister of War and Navy in Montero’s provisional government11. It is significant to note that Dr. Martinez had an 8-yr-old daughter who died on the 21st of January 1912. Historical sources record his departure from his post (and immediate departure from the country) to have occurred on the 19th or 20th so it is possible his daughter was critically ill or already on the verge of death when he abandoned his post. Further research on these details is underway.

- On the grounds of the change in the directorship of the War (ie: the appointment of Eloy Alfaro as Director of the War) three of the original five Cabinet ministers in Montero’s provisional government submitted to him a written document of resignation on January 19th, the day after the disaster at Yaguachi. 12. So, including Dr. Martinez, four of the five cabinet ministers resigned leaving only one of the original appointees. 13Montero promptly filled the vacant offices with replacements.

- Attempting to prevent yet another, possibly worse, battle- some of the notables of Guayaquil (ie: civilians) intervened. They convinced the consuls of Great Britain and the U.S. to negotiate a truce and act as guarantors of the agreement. According to this agreement -signed on January 22- Montero pledged to “cease hostilities, disarm his army and hand over the field in exchange for guarantees that he and his bosses would be able to leave the country without difficulty”14

But when more Army officers arrived shortly thereafter from Quito they disowned the agreement. In the press there were already bold demands for the lynching of the “Alfaristas” and soon it would be argued that the agreement had been the result of “foreign meddling” (ie: referring to the participation of the consuls of the U.S. and Great Britain). Alfaro was taken prisoner and when Montero learned of it, he voluntarily surrendered to share the fate of his leader. After some debate it was decided that only Montero would be prosecuted by a military court in Guayaquil. There were demands for a death sentence but the death penalty had recently been abolished and replaced by a maximum sentence of 16 years in prison. So Montero was sentenced to 16 years in prison. But the crowd congregated at the courthouse demanded nothing less than the firing squad for Montero. Amidst the courthouse melee a non-commisioned officer suddenly moved forward and shot Montero point blank.

Montero’s body was tossed out of the window to the mob, which beheaded it, dragged it through the streets to the Plaza Rocafuerte, poured kerosene upon it, and burned it there. Montero’s head and heart were embalmed and sent to Quito as trophies. Thus began the wave of barbarism which swept over the nation during this tragic month.

— from Spindler, Frank M., “Nineteenth Century Ecuador an historical introduction” p. 210

The “Barbaric Bonfire”

Subsequently, on January 26, Alfaro and several close supporters including even Luciano Coral editor of the newspaper “El Tiempo” were sent by train (the trans-Andean railroad which had been his life’s work) to Quito even though it was considered a foregone conclusion that they would face a lynching there in one way or another. On their arrival in Quito, they were thrown into prison but the prison was practically unguarded and the few soldiers guarding the gates had instructions not to offer resistance. The accounts of two historians, Spindler and Ayala Mora, are included below:

“Eight men entered Eloy Alfaro’s cell first and killed him; then Paez, Medaro Alfaro, Serrano, Coral and Flavio Alfaro were killed. Before his death, the mobsters cut out Coral’s tongue. The naked bodies of the slain were delivered to the multitude, who further dishonored them by castrating them and tossing their virile members in the air. ”

— from Spindler, Frank M., “Nineteenth Century Ecuador an historical introduction” p. 210

“The prisoners were delivered to the prison. They were not there for long. The building was practically unguarded, as the colonel had expressly rejected reinforcements. Moreover, the few soldiers guarding the gates had instructions to offer no resistance. The crowd penetrated the prison and launched an assault on the cells of Alfaro and then shot him in the forehead. Paez, who managed to fire off a revolver that he had hidden, fell next following the others. A woman stabbed Serrano, then drank the blood from the dagger. They cut out the tongue of the journalist Coral. Finally they killed Flavio Alfaro who was locked in a cell with a padlock.

Minutes later the cadavers were dragged down along along the crowded Rocafuerte Street. The people dragging the bodies shouted ‘Long Live Religion, Death to the Freemasons, Death to Foreigners’. Many women participated in the act; five of them dragged the corpse of Flavio. As the melee arrived at Santo Domingo, several groups took different routes but eventually all converged at El Ejido Park. There pyres were lit with the remains. Close to nightfall the remnants of the slaughter could be recovered.

The government authorities did nothing to impede the act…”

–from Ayala Mora “History of the Ecuadorian Liberal Revolution” p. 189

Further details on the murder

An article appeared two weeks later in the New York Times giving one of the most detailed descriptions of the murder:

The murdered Generals were subjected to frightful cruelties before being killed. Montero15, the first slain, was seized by the mob, which, after cutting off his head and tearing out his heart, poured kerosene upon his body and burnt it. At Quito, the capital of a country where capital punishment has been abolished, the proceedings were similar. The five Generals and two Colonels were subjected to all manner of tortures and mutilation before being slain. …the tortures were done with the care of inventors perfecting a new mechanism. The suffering men were permitted to hear the deliberations of their captors trying to decide what additional cruelty could be perpetrated. One of the Victims, col. Coral, whose tongue had just been cut out was placed on a stand and ordered to make a speech. When the seven officers at last succumbed the mutilated bodies were targets for the rage of the populace.

— from a New York Times article dated Feb 14, 1912

But this wasn’t all. After the murder, the body of Eloy Alfaro was dragged through the streets of Quito and finally the bodies were burned in a “Barbaric Bonfire” (as the author of a life of Alfaro would later title his biography). The site is today a public park called “El Ejido Park”.

Other Contemporary References

Two articles appeared in the New York Times in Connection with this Murder:

Storm Jail and Kill Ecuador Generals (1/29/1912 ) – pdf

Alfaro’s Wife testimony after murder – pdf

Over time public sentiment changed and the barbarity of the events of January 28th, 1912 -now known to all Ecuadorians as the “Arrastre” or dragging of Eloy Alfaro- were acknowledged. Although there is still a fanatical element in Ecuador, they are definitely in the minority and the name of Eloy Alfaro lives on in Ecuador today as a reminder of the fundamental human rights that were secured for all Ecuadorians by his efforts and the efforts of those who assisted him. The indignities he suffered in his death stand in stark contrast to the fundamental rights to human dignity that his “Alfarista” movement secured for all Ecuadorians.

- The event that triggered this “split” was the “Esmeralda” affair; Ecuador’s president Cordero (a “Progressive”) had arranged for Ecuador to act (for a fee) as an intermediary in the sale of a Chilean ship (the “Esmeralda”) to Japan. Chile wanted to sell the warship to Japan while simultaneously maintaining their pledge of neutrality toward the Sino-Japanese war so they approached Cordero and together they came up with a clandestine plan. Secret arrangements were made so that the transaction would take place quietly in the waters off the Galapagos. When Ecuadorians found out about it the public reaction was one of outrage. This transaction “…caused, or was made the excuse to cause, a revolution which was headed by General Eloy Alfaro. A year’s desultory fighting between the rival forces disturbed the troubled republic and as a result of the final battle the Government forces were overcome, and President Cordero abandoned his office and escaped from the country”. Since this scandal involved use of the Ecuadorian flag in exchange for a clandestine fee, it is also known as “The Sale of the Flag”. ↩

- NOTE: I have been unable to find independent confirmation of this affirmation of Alfaro’s religious convictions. However there is enormous evidence that when he became president Alfaro proceeded with great caution so as preserve religious freedoms. -pjc ↩

- Literally “The Law of the Dead Hands”. In the language of the time, the term “Dead Hands” was used to refer to the fact that the vast estates held by the Church in Ecuador were non-productive. While huge parts of the population were impoverished and without any property, these vast estates were for practical purposes “dead” in the “hands” of church authorities. ↩

- Ayala Mora: History of the Liberal Revolution in Ecuador page 147 (“the Succession after Plaza) ↩

- By this time Alfaro was a 70 year-old man and his nephew Flavio Alfaro was politically ambitious. Flavio had developed close ties within the ranks of the army. ↩

- Members of Alfaro’s closest circle, including Dr. Martinez, warned Alfaro of the impending coup but he brushed-off the danger insisting that they “wouldn’t dare”. Dr. Martinez’ son Ramon reported this fact regarding his father and historical sources support these reports (see eg. Spindler 1987, p.205). ↩

- Alfaro vacillated in this project of choosing a successor; he wanted to ensure continuation of the “Alfarista” liberal project after his exit but he no longer had many friends on whom he could rely to be faithful against the pressure from the “Plaza” strain of Liberalism. ↩

- Authority for this statement is Spindler, page 208. ↩

- This is according to the testimony of Miguel’s own son Miguel (jr.) ↩

- Yaguachi is located just outside of Guayaquil, about 15 miles to the northeast ↩

- “El coronel doctor Francisco Martinez Aguirre, apenas sabido el desastre de Yaguachi, tomo pasaje para el exterior, abandonando de hecho el cargo de ministro de guerra y marina” …in English: “The Colonel Dr. Francisco Martinez Aguirre, upon learning of the disaster of Yaguachi, secured passage out of the country abandoning thereby his charge as minister of the War and Navy”. -from p.147: El Mes Tragico:: compilación de documentos para la historia ecuatoriana. by Luis Eduardo Bueno – pub. 1916 Quito, ↩

- These ministers were Borja, Villamil, and Franco – ministers of Interior, Public Instruction, and Foreign Relations respectively. ↩

- It seems probable the resignation of these four ministers is attributable to the fact that upon his deposition and exile from the country in August of 1911, Alfaro had sworn in writing to have nothing more to do with the politics of Ecuador. Perhaps he now felt that this new situation of Civil War was so urgent that it invalidated his earlier oath …or perhaps his age was affecting his judgement (Historian Ayala Mora feels that by 1911 his judgement was impaired by age). In any case, he didn’t live long enough after this fateful decision to have communicated to posterity an explanation for this seemingly irrational action. ↩

- Ayala’s acount ↩

- Dr. Francisco Martinez Aguirre was appointed “Ministerio de la Guerra” in a provisional government that had been set up by Montero after the death of Estrada. This provisional government lasted for a very brief time, of course. ↩