Ecuador was made a Colony of Spain after the Spanish conquest in the mid 1500’s. Unlike the experience in Colonial North America, Colonial South America was not a haven for those seeking religious freedom; there was a Spanish Inquisition in the Spanish Colonies of South America. In the colonies of South America,

“The Church was the centre of colonial life. She governed in the spiritual order; imposed punishments, flagellations, exile and excommunication, and delivered unbelievers and sorcerers to the purifying care of the Inquisition.”

–from F. G. Calderon, “Latin America, its rise and Progress (1915)

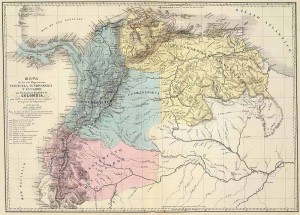

Independence from Spain did not come until three centuries later in 1822. From 1822 until 1830 Ecuador was a part of La Gran Columbia which was an attempt under Simon Bolivar to unite the territories that are today Venezuela, Panama, Columbia and Ecuador.

But by 1831, after the death of Simon Bolivar, Ecuador had become an independent nation-state.

An excellent brief overview of Ecuador’s history in the first century after independence was set down by Webster E. Browning PhD in 1920:

“The history of the republic has been turbulent, and revolution has succeeded revolution with wearying rapidity. The struggle, on the whole, has been between the Liberal and the Clerical parties, with first one and then the other in the antecedent. Even today [ie: 1920], with a Liberal constitution and with the Liberal party in power, the Clericals remain strong and are a force to be reckoned with in all endeavors to uplift and educate the people.

Perhaps no better insight into this turbulent history of Ecuador could be obtained than that which is secured through the study of the administrations of two of its presidents, Garcia Moreno, whose power terminated with his death by assassination in 1875, and Eloy Alfaro, who was done to death by the soldiers and mutilated by the populace in 1912, after having served two terms as president and secured the Liberal constitution by which the country is now ruled.

Garcia Moreno was the head of the Catholic party in Ecuador, and entirely under the domination of the clergy1. His only ambition seemed to be that of establishing more firmly the Church of Rome in all the affairs of state and it was largely due to his influence that the Concordat was finally established in 1863, giving to the Church what was practically supreme power over the State. As a matter of historical interest, and as showing how far fanaticism may go in fostering ecclesiasticism on a country, it will be well to quote here the first two articles of that Concordat which read as follows: –TERMS OF THE CONCORDAT

Art. I. The Roman Catholic and Apostolic religion shall continue to be the religion of the Republic of Ecuador, and it shall conserve forever all the privileges and prerogatives which belong to it, according to the Law of God and the canonical rules. Consequently, no other heretical worship shall be permitted nor the existence of any society condemned by the Church.Art. II. The instruction of the youth in the universities, colleges, faculties, public and private schools shall conform in all respects to the Catholic doctrine. In order that this may be assured, the Bishops shall have the exclusive right to designate the texts that shall be used in giving instruction, both in the ecclesiastical sciences and in the moral and religious instruction.

In addition, the diocesan prelates shall conserve the right to censure and prohibit, by means of pastoral letters and prohibitive decrees, the circulation of books or publications of any nature whatsoever, which offend the dogma or the discipline of the Church or public morals.

The Government shall also be watchful and shall adopt the necessary measures to prevent the propagation of such literature in the country.”— from Webster E. Browning Ph. D “The republic of Ecuador: social, intellectual and religious conditions today” (1920)

This Concordat (see full text here) was the cause of intense difficulties and disruption in the political and social life of Ecuador in the 19th century and beyond. It deprived Ecuadorians of freedom of conscience and expression and of many fundamental human rights.

More detailed coverage of Garcia Moreno and the presidents who succeeded him is provided elsewhere on this site:

President Gabriel Garcia Moreno (1861-1875)

President Veintemilla (1876-1883)

President Caamaño (1883-1888)

President Antonio Flores Jijón (1888-1892)

President Cordero (1892-1895)

Garcia Moreno’s first term had been so repressive and his tactics so brutal that he and his partisans within the overall “conservative” movement came to be known as the “Terrorist Party”2. After Garcia Moreno’s assassination, President Veintemilla initially attempted to reverse many of his repressive policies but this effort met with so much resistance from entrenched powers in Ecuador that Venitemilla capitulated and gave up on the effort. In the mid 1880’s, President Caamaño – who was hailed as “Conservative and Catholic” – encountered partial success in his efforts to restore many of the policies of Garcia Moreno including renewal of the concordat but by this time the opposition was gathering strength in Ecuador and so within the “conservative” party a faction formed aimed at pushing the conservative party in a more moderate direction. This faction within the conservative party was known as the “Progressives” and the next two presidents were from the “Progressive” faction of the conservative party. But during the term of President Cordero (1892-1895) the alliance between the “progressives” and the “terrorists” within the “conservative” movement weakened and by 1895 it broke as a result of a scandal that came to be known as “The sale of the Flag” or the “Esmeralda Affair”.

The “Esmeralda Affair” (or the “Sale of the Flag”)

President Luis Cordero Crespo’s presidency collapsed on discovery of a clandestine sale of a Chilean Battleship

During the presidency of Cordero arrangements had been made for Ecuador to act as a secret intermediary in the sale of a Chilean battleship (the “Esmeralda”) to Japan – an illegal transaction due to Chile’s declared neutrality toward the Sino-Japanese War. Secret arrangements were made so that the transaction would take place quietly in the waters off the Galapagos using Ecuador’s flag instead of Chile’s (for a price). When Ecuadorians found out about it there was an outrage (See NY Times articles in notes below). Cordero was ousted from office3 (April 16, 1895) and after a considerable period of fighting, Eloy Alfaro -newly returned from Panama- emerged victorious and seized the presidency. During the ensuing “Liberal Revolution” sweeping changes were made in the relationship between church and state. But after Alfaro’s first term there was a breach in the Liberal party under the presidency of President Plaza who did not share in Alfaro’s determination to lift the burden from Ecuador’s poorer and underprivileged classes. In 1912, after a coup, the complex web of power structures in Ecuador exploded in a month of barbarism culminating in the brutal mob execution and “dragging” of Alfaro and his closest supporters.

References:

The Esmeralda Affair – NY Times Articles:

Initially, in late 1894 an article was published in the New York Times about the sale of the Esmeralda with no mention of the scandal that would subsequently surround the transaction. However a few months later another article was published explaining the scandal in the most minute detail. Click the links below to see the actual articles (credits: NY Times):

US State Department Web Page on Ecuador

NOTE: The section on President Cordero was corrected (2018) to remove implications that he had been directly responsible for the “Esmeralda Affair”.

Notes:

- Dr. Browning’s wording here is somewhat inaccurate. Although President Garcia Moreno granted sweeping powers to the Roman Catholic Church in Ecuador, not all clergymen agreed with him. But Garcia Moreno did get rid of many of the clergymen who disagreed with him, replacing them with clergymen imported from Europe. ↩

- For more details on the dating and background of this “terrorist” label, see Enrique Ayala Mora’s “Political Struggle and Origin of the Parties of Ecuador” (“Lucha Politica y Origin de los Partidos en Ecuador”) p. 157-8. ↩

- Interestingly, on April 17 1895, the very next day after Cordero Crespo signed his resignation from the presidency, Japan and Qing China signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki ending the Sino-Japanese War. ↩